(From

top) Zeng Yun Hui, Zeng Bing Yuan’s sister. (Courtesy of her daughter Xue Ya Zhen.); Zeng Bing Yuan’s last photo in early 1980s. (Courtesy of Lirio Chan-Dapulag); Photograph sent by Zeng Bing Yuan to his sister in Xiamen showing his family in Bobon, Northern Samar. (Photo courtesy of Zeng Ya Zhen, Yun Hui’s daughter.); and The author (rightmost) and his family visit to Lirio Chan-Dapulag (seated, third from left) at her residence in Bobon, Northern Samar in November 2009.

Screen grabs of the video showing the moment the descendants of Zeng Bing Yuan and his sister Zeng Yun Hui were reunited. (Shenzhen TV, Guangdong province, China, Jan. 20, 2010.); Owen Chuan (詹仙友),

Xiamen’s relative finder; featured story: Jocelyn de Torres and her Chinese Aunt Xue Yun Zhen being interviewed by a Fujian TV reporter; story covered by Xiamen Daily newspaper (廈門日報); surviving children of Zeng Yun Hui – Xue Ya Zhen, left, and Xue Yun Zhen, right – flank Conchita Chan (one of the daughters of Zeng Bing Yuan); and dinner with the families of Zeng Yun Hui’s deceased son, Xue Fu Ping, during the Chinese New Year festival in Xiamen City

————————————————————————————————————————–

By Eduardo Chan de la Cruz Jr.

Published by Tulay Fortnightly

Chinese Filipino Digest – April 9-22, 2013 ~ Volume 25 ~ Issue No. 21

http://www.kaisa.org.ph:16080/tulay/archive/2013/040913/040913-V25N21.html

————————————————————————————————————————–

Most of the people I have helped to find their Chinese relatives had links to rural China. Either their parents or grandparents grew up in an agricultural village, or had once lived in one.

For those unfamiliar with Tsinoys’ humble beginnings, searching for roots in China may seem daunting. Actually, it is not, specially if one has a good understanding of the language. Just get hold of old letters from the mainland; usually, the village address is on the envelopes. These villages are same-surname-villages, everybody knows everybody.

Then there are exceptions.

The family of my grandfather Zeng Wen Yi’s (曾文藝) friend is one example. His name is Leonardo Chan or Chan Ping Guan (Zeng Bing Yuan 曾炳源); he is originally from Xiamen. He settled in Bobon, Nothern Samar, a town next to my hometown.

Most people visiting the Minnan speaking areas of Fujian province enter China at Xiamen and are familiar with this large, bustling and fast changing metropolis. Bing Yuan may not have recognized it if he were alive to see Xiamen today.

In November 2009, my China cousins came to visit us in Samar. We toured them around the residences of families in our area with the same surname as ours: Zeng (曾).

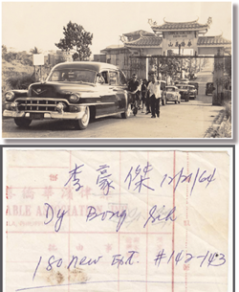

One of them was Lirio Chan-Dapulag, Bing Yuan’s granddaughter. At her house, she showed us some documents she had been keeping, documents that included letters from her grandfather’s sister, Zeng Yun Hui (曾雲惠),

from Xiamen.

As a young boy in the early 1900s, Bing Yuan accompanied his uncle to seek better life in the Philippines. He had left behind in China his sister Yun Hui.

For decades, the two stayed in close touch. Bing Yuan made sure his children recognized their Chinese kin and involved his eldest son, and Chan-Dapulag’s father, Jose (Zeng Fu Xi 曾扶西), in writing correspondence to China.

In the early 1980s, both Bing Yuan and his sister were feeble from old age, so Jose made arrangements for his grandfather’s travel back to China. But in those years, getting travel documents proved problematic. In the end, both brother and sister died without a chance to meet in person.

With the elders gone, Jose ceased writing to China. He too died in early 2000s. None of Jose’s children or their cousins knew how to reconnect with their overseas relatives but remained curious about their distant kin.

I knew it would be extremely difficult to look for Bing Yuan’s kin in a metropolis. I would have quickly given up, but it is unusual to see someone as eager as Chan-Dapulag to know her roots.

Happily, the hunt for her kin did not end in vain: it opened up an opportunity of new discoveries and a wonderful adventure for Chan-Dapulag’s family.

It was Dec. 12, 2009. How to start my search? I was stumped. I browsed the Internet and found a discussion forum http://www.askmehelpdesk.com. In it, someone in the United Kingdom was asking for help looking up Xiamen relatives.

Someone in China had responded to his inquiry, saying he had been helping foreigners find their roots in China and was willing to help. There was an email address, so I wrote to him about my unusual hobby: relative finder.

We exchanged experiences of relative searching and got to know each other: Owen Chuan (Zhan Xian You 詹仙友) an ethnic Hakka who grew up in Fujian’s mountainous region.

Hakka people are well known for very close family bonds, closer than the usual Chinese ties. Just look at their enclosed one-building villages called Fujian Tulou (福建土樓), earthen rural dwellings built between the 12th and 20th centuries. These are three to five storeys high housing up to 80 families!

Before long, Chuan and I agreed on a collaborative project: to find Chan-Dapulag’s grandaunt.

He checked the old address from the letters I gave him and found the old house in which Yun Hui stayed. But it has already stood empty for many years.

I sent Chuan scanned copies of Chan-Dapulag’s documents to give him more information to work with. Chuan contacted the police to look for the names we found in the letters as well as asked his friends in media to help broadcast our search. On Jan. 5, someone called Chuan to say he is Yun Hui’s grandson.

The following day, Chuan visited their house and found family photographs sent by Jose in the 1970s.

Shenzhen TV, one of the media groups that helped broadcast the search offered Chan-Dapulag’s family free airplane fare to China to cover the reunion they organized.

Three relatives volunteered to come: a cousin, Nelly Chan-Cruzat, from Batangas; Chan-Dapulag’s sister Jocelyn Chan-de Torres from Richmond, Canada; and her Auntie Conching (Conchita Chan, Jose’s younger sister) from Antipolo. Chan-Dapulag herself could not go; her husband was very ill then.

Not only did Chuan and I helped with the search, we ended up acting as travel agents ourselves!

He helped organize the event with the TV station while I helped the Philippine delegation put together their travel documents, such as passports, visas and letters.

Before she left I met up with Chan-Cruzat to provide her some final tips about traveling to China and lent her my handheld digital dictionary: it comes in really handy for those of us who cannot understand Chinese.

The three ladies met up in Hong Kong and traveled together to Guangzhou on Jan. 28. Chuan was also there to guide the representatives of Yun Hui’s daughters.

Too old to travel, Yun Hui herself could not be there. On the evening of Jan. 30, both families met for the first time during a live Chinese New Year show at Shenzhen TV station. The show was broadcast all over China, Hong Kong and Macau. Segments of the show were made available via Internet video upload.

The next day, relatives took the three ladies to Xiamen. There, they were treated to the weeklong Chinese New Year festivities.

As well, there were additional moments of fame when they were interviewed by the Xiamen Daily newspaper and Fujian TV.

They say time goes fast when you are having fun. With all these happening in just over two months, time’s passage might have felt more like a flash of lightning for the Chan family of Bobon!

It was a-nother wonderful moment for me to have helped reunite yet another family. It was especially moving to see this happen during the Chinese Spring Festival.

This time, it was extra special because I met Chuan, a new friend and Chinese counterpart who helped make it possible.